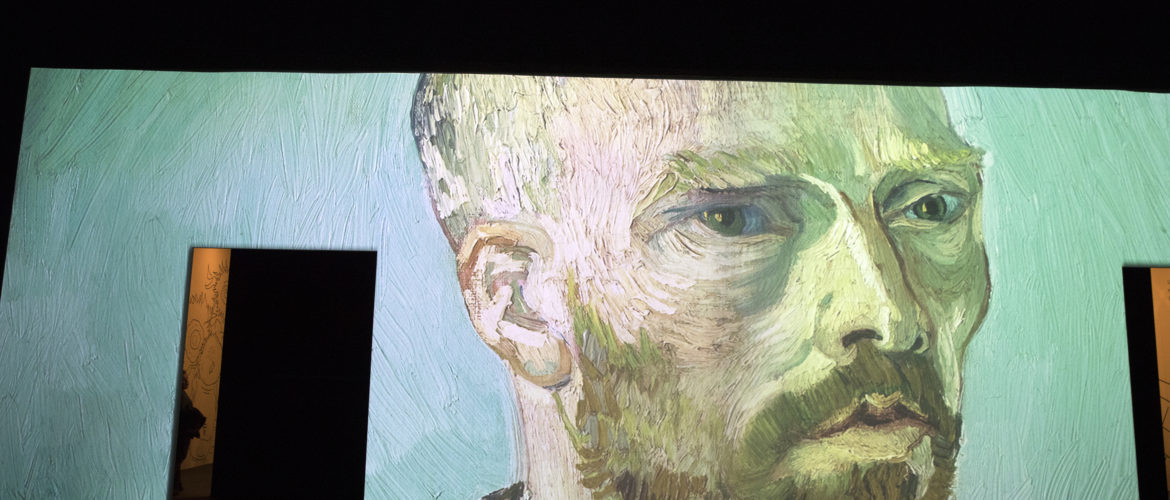

Creativity and Mental Illness: How True Is a “Mad Artist” Stereotype?

Vincent van Gogh’s bipolar disorder, Edvard Munch’s anxiety, and Claude Monet’s attempted suicide made many people of the past foster the notoriously known stereotype of a “mad artist.” Creativity and mental health have been the focus of many pieces of research for years, especially in relation to art therapy, and yet the firm link between the two hasn’t been proved by any of them. In all fairness, some similarities can look like a cause-and-effect relationship, but it fades away when you look into the context of the problem.

Madness in Art: What Does It Mean to Be a “Mad Artist?”

A whole lot of studies examined the connection between mental illnesses and creative activities. A portion of those found the link between creativity and mood diseases such as depressive and manic-depressive disorders. The list of interconnected mental illnesses also includes bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. While researchers succeeded in connecting the dots in some very specific cases, especially schizophrenia-related studies, the whole picture appears rather blurred.

The concept of a “mad artist” fails to explain how mental health issues contribute to painters, sculptors, and writers. It usually enters the domain of emotions where it is hard to establish a correlation between specific triggers of creativity. That is why people with mental disorders can or cannot be creative, and the source of their assisted imagination can be much deeper and more complex than what we know now.

Even if a “mad artist” paradigm exists, people fail to choose the right methodology to understand it. The thing is that mental illnesses are not the source of creativity but rather their aid. Such an approach is much healthier as it alludes to the fact that creativity exists without some internal issues, which is true due to the lack of evidence to support the opposite cause.

Looking at the Other Side of the Question

Accents start shifting when you look at those famous artists who didn’t have any recorded mental issues and were prolific and successful. Of course, that doesn’t disprove the hypothesis of a “mad artist,” and yet it encourages modern scientists, researchers, and even ordinary people to take the discussion to the next, more complex level. Hopefully, we will get more evidence that will explain the similarities and differences between mental health and creativity in the future!