De Stijl: Art Deco, Geometric Forms, and Piet Mondrian

If you look at art history, you can notice one peculiar rule: movements are subdued by other movements, bringing contrast to establishments, techniques, and approaches that were perceived as canonical and traditional before. A good example of such a reaction in recent modern art is the relation of De Stijl to Art Deco. While the connection between the two is mostly symbolic, the beginning of the century was marked by its shifting trends towards abstraction. Let’s learn more about the Netherlands-based movement and its place in history.

De Stijl and Art Deco

Admiration of functional objects and modernity were the principal features of Art Deco, which spanned the 1920s. It was itself an answer to Art Nouveau, with the latter focusing on carves and the natural environment. If you compare De Stijl and Art Deco, you might consider them to be conceptually similar, and you will be right. At a glance, they stem from the same philosophical discoveries of the new age. However, they were also very different, especially when you take into account the directions in which the movements headed. The fact is that the Dutch approach aimed to find the equilibrium between art and life, aesthetics and society. It was indeed a symbol of the second industrial revolution, but it wasn’t meant to be practical or functional whatsoever.

Geometric Forms

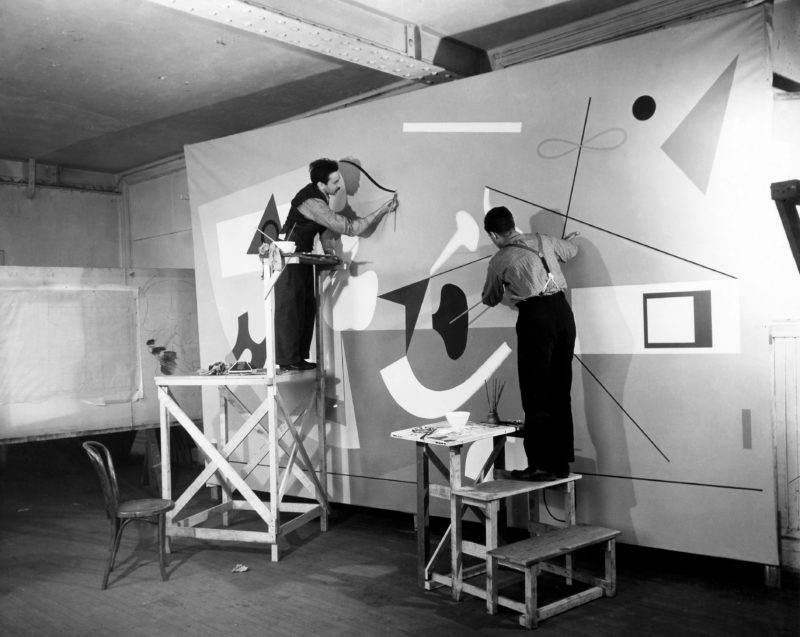

De Stijl is all about well-measured shapes, geometric lines, asymmetrical structures, and simple colors. Such a combination was not something people of that time were used to seeing often. The violation of established rules in painting, sculpture, and architecture was an exotic experiment that some people admired, some despised, and some others just couldn’t understand. Diagonal lines allowed artists to imbue their art with their utopian visions of the perfect society. Those were deeply influenced by World War I.

Piet Mondrian

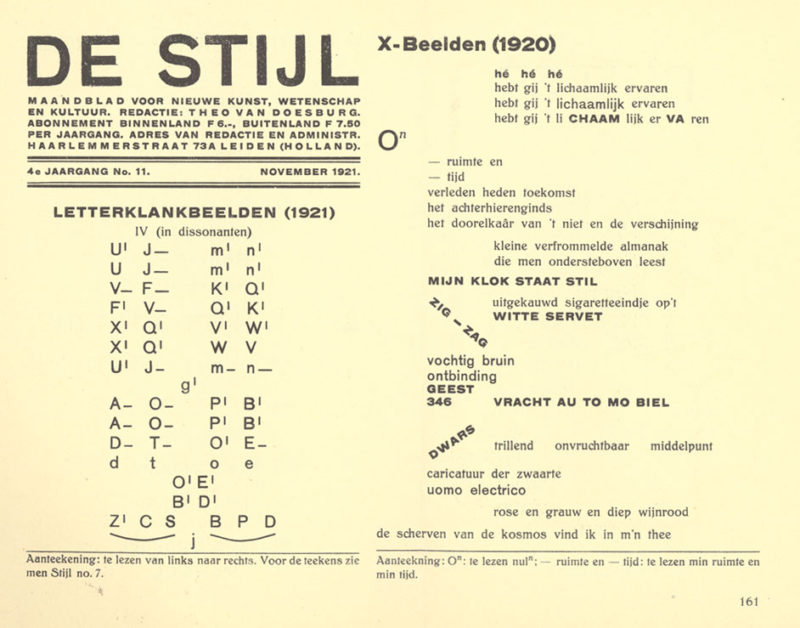

Piet Mondrian was arguably the brightest figure of the De Stijl movement. Together with J. J. P. Oud and Vilmos Huszar, he adopted the elements of Dadaism, Suprematism, Cubism, and Neoplatonism to create the notion of the “ideal” forms, which turned out to be asymmetric geometric lines. It all started from the journal devoted to abstraction in art. Later on, the artists started presenting their works to the world, meanwhile drawing more attention from the public and other creators from the community. Even though the movement didn’t last long (approximately until 1930), it influenced quite a few artists of that time, who would later develop new forms. Those were Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, Barnett Newman, Dan Flavin, and Donald Judd, among others.